Numerous clinical procedures require incisions of the body wall. Consequences of these incisions depend on the direction of muscle fibers and the location of neurovascular bundles. Accordingly, this exercise focuses on the anatomy of the abdominal body wall.

The rectus abdominis muscle runs on both sides of the midline from the rib cage to the pubis. Notice how the muscle fibers run in the superior/inferior direction. Note that the midline is not covered by muscle. Confirm this by rotating the image to a view slightly off anterior to the right, a right anterolateral view, and a right lateral view. To understand the sheath of this muscle, we have to consider the muscles of the lateral abdominal wall.

Wrapping around the lateral body wall are three flat muscles: the external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis. Mouse over them on the cross-sectional images. In the 3D view, note how the fibers of the external oblique travel inferiorly as they approach the rectus abdominis. Remove the right external oblique to expose the internal oblique muscle. In the 3D view, note how the fibers of the internal oblique travel superiorly as they approach the rectus abdominis muscle. Switch back and forth between this and the previous link to convince yourself that the fibers of the external and internal oblique muscles are roughly perpendicular to each other. Repeat this for the transversus abdominis muscle. Be sure to examine the cross-section views as you add and subtract these muscles.

What is the advantage of this crisscrossing pattern?

It's the same idea as plywood. By orienting each ply (muscle layer) in a different direction, force is exerted in multiple directions when the muscles contract - creating a very strong wall.

How can an incision be made here without injuring the muscles?

The surgeon splits fibers of the muscles layer-by-layer. First, the external oblique is incised parallel to its fibers and the fibers are spread apart. This is a muscle-sparing incision, because very few fibers are damaged. To avoid dividing (cutting across) the fibers of the internal oblique, the orientation of the incision must be turned 90°, and so on.

For a demonstration of the McBurney incision click this link

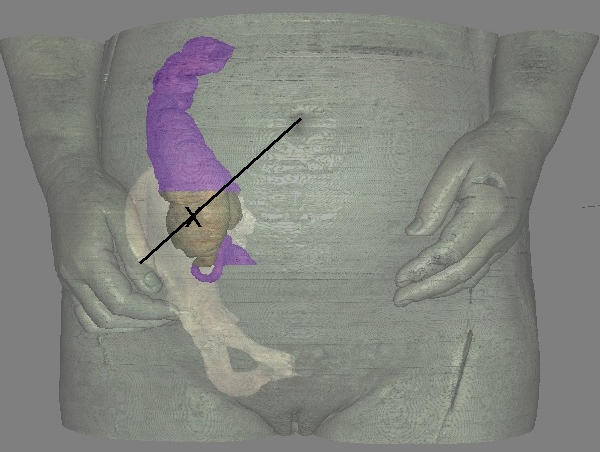

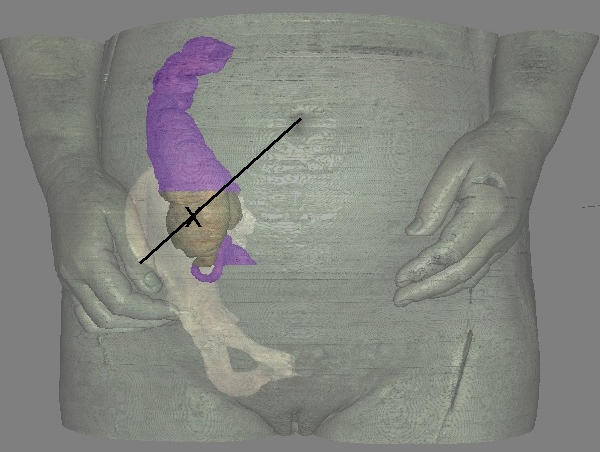

The McBurney incision creates a window into the abdomen to access the appendix. The following image shows how McBurney's point is located along a line between the anterior iliac spine and the umbilicus. The appendix is the worm-like structure seen below the cecum (brown).

Besides being a muscle-sparing incision, the McBurney incision places few nerves and vessels at risk. View a dermatome map to see how a window-like incision at the "X" would affect only the T11 or T12 neurovascular bundle.

Observe the fibers of the rectus abdominis muscles, which lie parallel to the midline.

Which function of this muscle is enabled by this orientation?

Flexion (forward bending) of the trunk.

The rectus sheath is derived from the three lateral muscles discussed above. They are attached to the midline by broad, flat tendons. Typically a muscle tendon is cylindrical, but when they are broad and flat we call them an aponeurosis. Add the aponeuroses of the lateral abdominal wall muscles. Notice you can no longer see the fibers of the rectus abdominis muscles, but there is still a gap at the midline. Confirm this by rotating the image slightly toward a right anterolateral view. The fibers of the aponeuroses of the right and left sides actually cross the midline to interweave with one another and form a very strong structure called the linea alba. The linea alba is hard to see in the cross-sectional images, but has been placed in the crosshairs. Use mouse rollovers to define the extent of this thin structure.

Examine the rectus sheath more closely by removing the aponeuroses one by one. First, remove the left external oblique muscle and its aponeurosis. Note how the rectus abdominis muscle is still covered anteriorly by the aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle. Second, remove the left internal oblique muscle and its aponeurosis, and the right external oblique muscle and its aponeurosis. Note the view of the fibers of the left rectus abdominis muscle is unobstructed superiorly, but not inferiorly. The reason is that the aponeurosis of the transverse abdominis muscle passes anterior to the rectus abdominis muscle inferiorly, but posterior to the rectus abdominis muscle superiorly. In contrast, the aponeuroses of the external and internal oblique muscles pass anterior to the entire length of the rectus abdominis muscles. Remove the transversus abdominis muscle including its aponeurosis. Quiz yourself by using mouse rollovers to reveal the identity of all structures in the 3D view.

If we remove the skeletal system and take a posterior view of the abdominal muscles, we can see the posterior rectus sheath. Mouse over the superior part of the rectus sheath to identify the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis muscle. Mouse over the inferior part of the rectus sheath to confirm it is absent. The transition occurs at the arcuate line. Now remove the left transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis. Note the appearance of the internal oblique muscle and its aponeurosis. It forms part of the posterior sheath! An explanation for this appearance is provided by thinking of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle is two layers. Both layers travel superficial to the rectus abdominis muscle inferior to the arcuate line, but one layer travels deep to the rectus abdominis muscle superior to the arcuate line. Remove the internal oblique muscle and its aponeurosis.

An anastomosis of two vascular bundles is found between the posterior rectus sheath and the rectus abdominis muscle. To see them, we will go back to an anterior view. In principle, we should be able to see the superior and inferior epigastric arteries and viens by removing the anterior rectus sheath and rectus abdominis muscles. Unfortunately, the image data is not segmented that way and we removed all the rectus sheath. For clarity, the peritoneal fat was highlighted as a backdrop. Now, view the vessels from the posterior side with the fat and aponeuroses removed. The source of the superior epigastric artery is the subclavian artery via the intercostal artery. The source of the inferior epigastric artery is the external iliac artery. Both vessels become too thin to trace to their anastomosis. Notice that they travel inferiorly/superiorly and do not cross the midline. These vessels also anastomose with the intercostal vessels from T7 to T12 as they course along the anterior abdomenal wall. (They are too small to see in this data, but T10 heads towards the umbilicus and T12 heads towards the pubic symphysis.) Consequently, the intercostal neurovascular bundles also fail to cross the midline.

A patient suffers abdominal trauma and the surgeon must enter the abdomen safely and quickly. Where can an incision be made that will not divide (cut) nerves, vessels, or muscles?

The midline through the linea alba.

A rectus abdominis muscle can be used for reconstructing a breast following mastectomy. The muscle is detached form its inferior insertion and the inferior epigastric vessels are ligated and divided. The muscle is then slid under the skin into the chest. How will the tissue receive a blood supply?

The superior epigastric vessels are still intact.

A Kocher incision is made parallel to the right subcostal margin (where the costal cartilages of ribs 7-10 fuse and travel superomedially to the sternum). This gives access to the gall bladder and part of the liver. For greater access to the liver, the incision (Chevron incision) is lengthened from midaxillary line to midaxillary line, one inch inferior and parallel to the subcostal margin. Are these incisions muscle sparing or muscle dividing?

Unlike the McBurney incision (which separates muscle fibers), these long incisions must divide (transect) the external oblique and transversus abdominis (and for the Chevron, the rectus abdominis) muscles. As a result, a scar will form to reconnect the divided muscles thereby weakening them.

For a demonstration of the Chevron incision click this link

Will the Chevron and Kocher Incisions divide any neurovascular bundles?

The neurovascular bundles of T7 - T10 will be divided, resulting in a loss of sensation along the anterior abdomen and atrophy of muscles distal to the incision.

To hide the scar of a Caesarean section, the Pfannenstiel incision is made transversely through the skin, just above the pubic symphysis (below the bikini line). The skin is spread and the direction of the incision is rotated 90° to divide the midline. Why is the deep incision made in the superior/inferior direction?

The deep incision divides the linea alba, thereby avoiding the rectus abdominis and any neurovascular structures.