Digestive System

Directions

- Print this PDF worksheet for a hardcopy guide as you work through this lesson.

- Within the lesson click the red linked headings to bring up the desired starting point within the cadaver for your work.

- Use the provided images on the worksheet to annotate and identify specific anatomical structures.

Digestive system anatomy can be subdivided into two complementary halves, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (also known as the alimentary canal), and accessory organs. The GI tract is the physical pathway from mouth to anus through which our food enters and is processed. The accessory organs participate in the digestive process but never really "contain" digesting food. Our teeth, liver, and pancreas are only three examples, we'll examine these and several more.

Let's begin with an examination of these organs:

- Mouth - Obviously the "mouth" is a rather general term. It is part of the alimentary canal BUT it is a relatively complex structure composed of several different organs. The palate forms the roof of the mouth. The two parts of the palate are the hard palate and the soft palate. The palatine bones and palatine process of the maxillae underlie and support the hard palate. The soft palate is a mobile fold formed mostly of skeletal muscle. The finger-like uvula projects downward from the free edge of the soft palate. The soft palate rises reflexively to close off the nasopharynx when we swallow. The palatopharyngeal arches anchor the soft palate to the posterior tongue. This forms the arched area of the oropharynx that contains the palatine tonsils. With a flexible tongue you can easily feel the hard palate along the roof of your mouth and the soft palate near the back.

- Esophagus - From the mouth, food passes posteriorly into the oropharynx and then the laryngopharynx. These are common passageways for both air and food. The esophagus is a muscular tube about 25 cm long. It is collapsed when not involved in food propulsion. After food moves through the laryngopharynx, it is routed posteriorly into the esophagus as the epiglottis closes the larynx off to food entry.

-

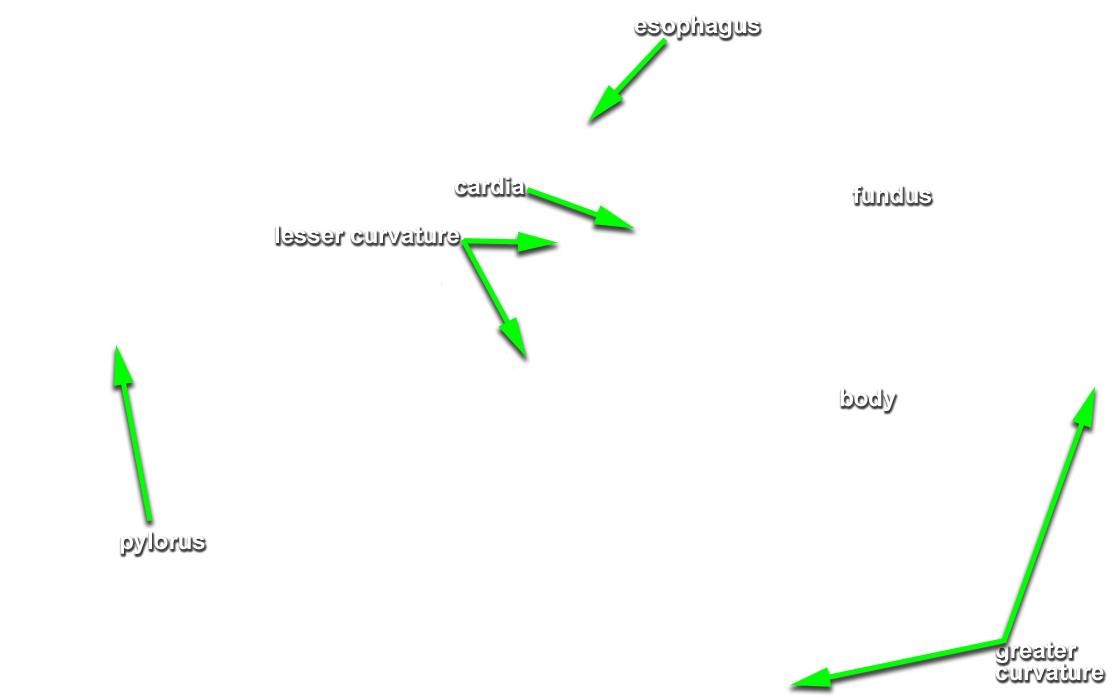

Stomach - The esophagus empties into the stomach. The gastro-esophageal sphincter acts as a valve.

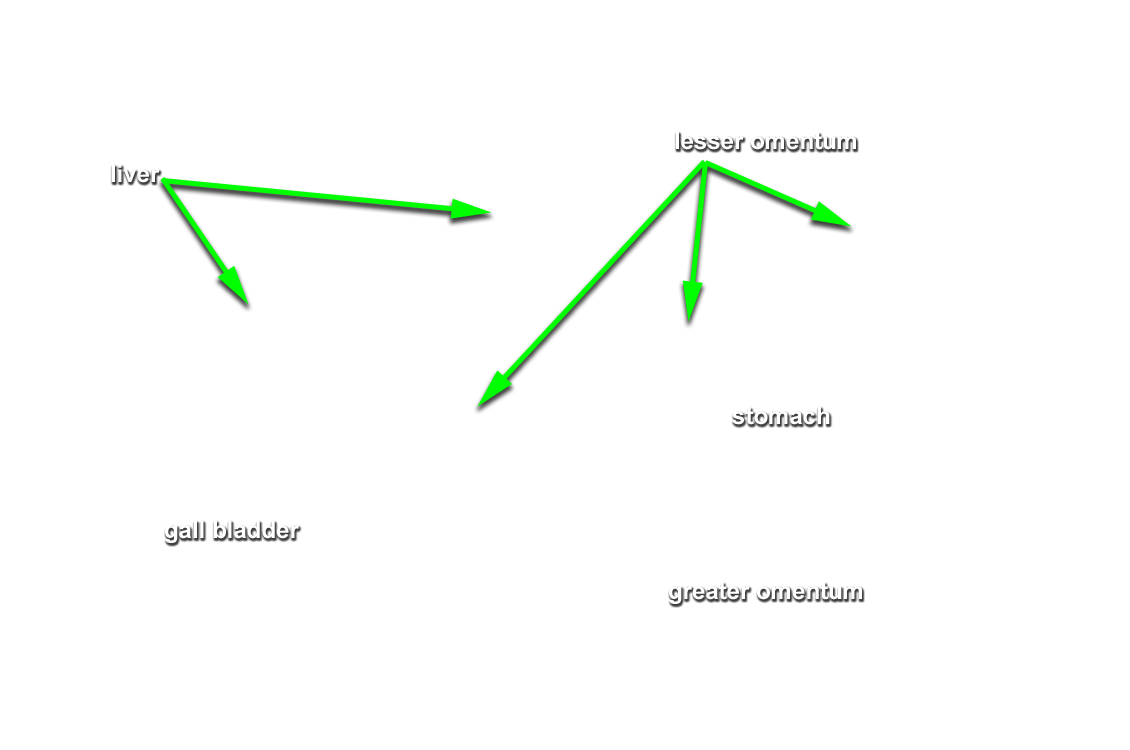

The lesser omentum is a mesentery that runs from the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach where it becomes continuous with the visceral peritoneum covering the stomach.

Identify each of the following and label them on your worksheet.

- Cardia - This is the superior (entry) region of the stomach

- Fundus - The fundus is the rounded upper portion of the stomach superior to the cardiac region.

- Body - The central portion of the stomach is the body.

- Pylorus - The pylorus is the inferior portion of the stomach that connects to the duodenum (the first portion of the small intestine). The pyloric sphincter regulates the movement of chyme (stomach processed food) from the stomach to the small intestine.

From the transverse cross section, notice the internal stomach walls are large longitudinal folds. These are called the rugae. These expand like an accordion when the stomach is distended with food.

-

Small Intestine - Identify each of the following in your specimen. The best way to do this is to work your way from superior to inferior by dissecting out the stomach then clicking away one piece of pipeline at a time.

- Pyloric Sphincter (Orifice) - This regulates the flow of chyme (stomach processed food) into the small intestine.

- Duodenum - This is the first, and shortest, subdivision of the small intestine.

- Jejunum - This is the second subdivision of the small intestine. It is about 2.5 meters (8 feet) in length.

- Ileum - This is the third and longest subdivision of the small intestine. The ileum is about 3.6 meters (12 feet) in length.

The support mesentery is not visible in your specimen, again, it is just too fragile to survive the dissection process. The jejunum and ileum hang from the posterior abdominal wall by this fan-shaped membrane.

-

Large Intestine - We'll begin where we left off with the small intestine at the distal ileum.

- Cecum - The ileocecal valve controls passage of small intestine contents into the cecum.

- Appendix (Vermiform Appendix) - Attached to the inferior aspect of the cecum is this small, vestigial coiled tube. With some frequency, the lumen (opening) to this tube becomes obstructed and infection occurs within, appendicitis. Surgical removal is necessary (appendectomy) which can now be done laparoscopically. This is one of two surgical removal procedures done to our specimen. We'll discover another with the reproductive system.

- Ascending Colon - From the cecum the colon rises up the right side of the abdomen to the level of the kidney.

- Transverse Colon - The right colic (hepatic) flexure is where the colon turns and becomes the transverse colon which passes laterally across the abdominal cavity.

- Descending Colon - The left colic (splenic) flexure where the colon turns again to form the descending colon which travels inferiorly along the left side of the abdomen.

- Sigmoid Colon

- Rectum - Provides feces storage.

- Internal & External Anal Sphincters - Controls the rectum.

We're going to focus on four major digestive accessory organs, salivary glands, liver, gall bladder, and pancreas.

-

Salivary Glands - Salivary glands produce and secrete saliva. Saliva cleanses the mouth, dissolves food chemicals so that they can be tasted, moistens food and aids in compacting it into a bolus (small round ball of food prepared by the mouth). Saliva also contains enzymes that begin the chemical breakdown of starchy foods.

- Parotid Glands - Mumps is an inflammation of the parotid glands caused by the myxovirus which spreads from person to person in saliva.

- Submandibular Glands

- Sublingual Glands

- Liver - Weighing in at 1.4 kg (3 lbs), the liver is the largest gland in the body. Located under the diaphragm, the liver lies almost entirely within the rib cage. Typically, the liver is said to have four primary lobes. The right lobe is the largest of these. Separated by a deep fissure, the left lobe is the second largest. The caudate and quadrate lobes are smaller and posterior, but not marked within your specimen. The liver removes worn out red and white blood cells as well as phagocytizes bacteria and other foreign matter in the venous blood draining from the gastrointestinal tract.

- Gallbladder - Tucked beneath the right lobe of the liver, the gallbladder stores and concentrates (up to 10x) bile produced by the liver.

- Bile Conduction - As previously stated, bile is produced by the liver and stored by the gallbladder. It emulsifies fat droplets in the small intestine. Clearly, ducts are needed to move bile from production to storage then to work. Dissect away the right and left lobes of the liver as well as the falciform and round ligaments. As you can see, the falciform ligament separates these two lobes of the liver. The round ligament is a fibrous remnant of the fetal umbilical vein. Dissect away the transverse colon, too and reveal the following structures:

- Hepatic Ducts (Right & Left) - Bile drains from the right and left lobes of the liver into their respective hepatic ducts.

- Common Hepatic Duct - The right and left hepatic ducts join to form the common hepatic duct which conducts bile to the next duct junction.

- Cystic Duct - This duct conducts bile in two directions. Newly formed bile is conducted from the common hepatic duct to the gallbladder and concentrated bile is released during digestion when the hepatopancreatic sphincter that guards entry to the duodenum is opened.

- Bile Duct - The bile duct conducts bile from the gallbladder to the duodenum during digestion. You'll need to dissect away the duodenum in order to reveal this duct.

-

Pancreas - Nestled in the curve of the duodenum, the pancreas is the third accessory digestive organ we'll examine. You can locate the pancreas from the anterior perspective but you'll see more of it by flipping your specimen over to the posterior view.

- Pancreatic Duct - Dissect away the pancreas to reveal the pancreatic duct that drains pancreatic juice from the pancreas to the bile duct just as it enters the duodenum. As previously mentioned, the hepatopancreatic sphincter regulates release into the duodenum during digestion.

Much of the alimentary canal organs are suspended within the peritoneal cavity by a mesentery. These organs, like the stomach, are called peritoneal organs.

Other parts of the digestive system originate in the cavity but then adhere to the dorsal abdominal wall. In so doing, they lose their mesentery and come to lie posterior to the peritoneum. These organs are called retroperitoneal organs. These include parts of the intestine and nearly all of the pancreas.

That brings our romantic journey through the alimentary canal to an end. I believe that gives a bit to digest at this point. :-o (If that doesn't give you acid reflux, nothing will!)

Self-Test Labeling Exercises